Chronicling domestic violence in Australia | Book Club Reviews Manjula Datta O’Connor’s ‘Daughters of Durga’

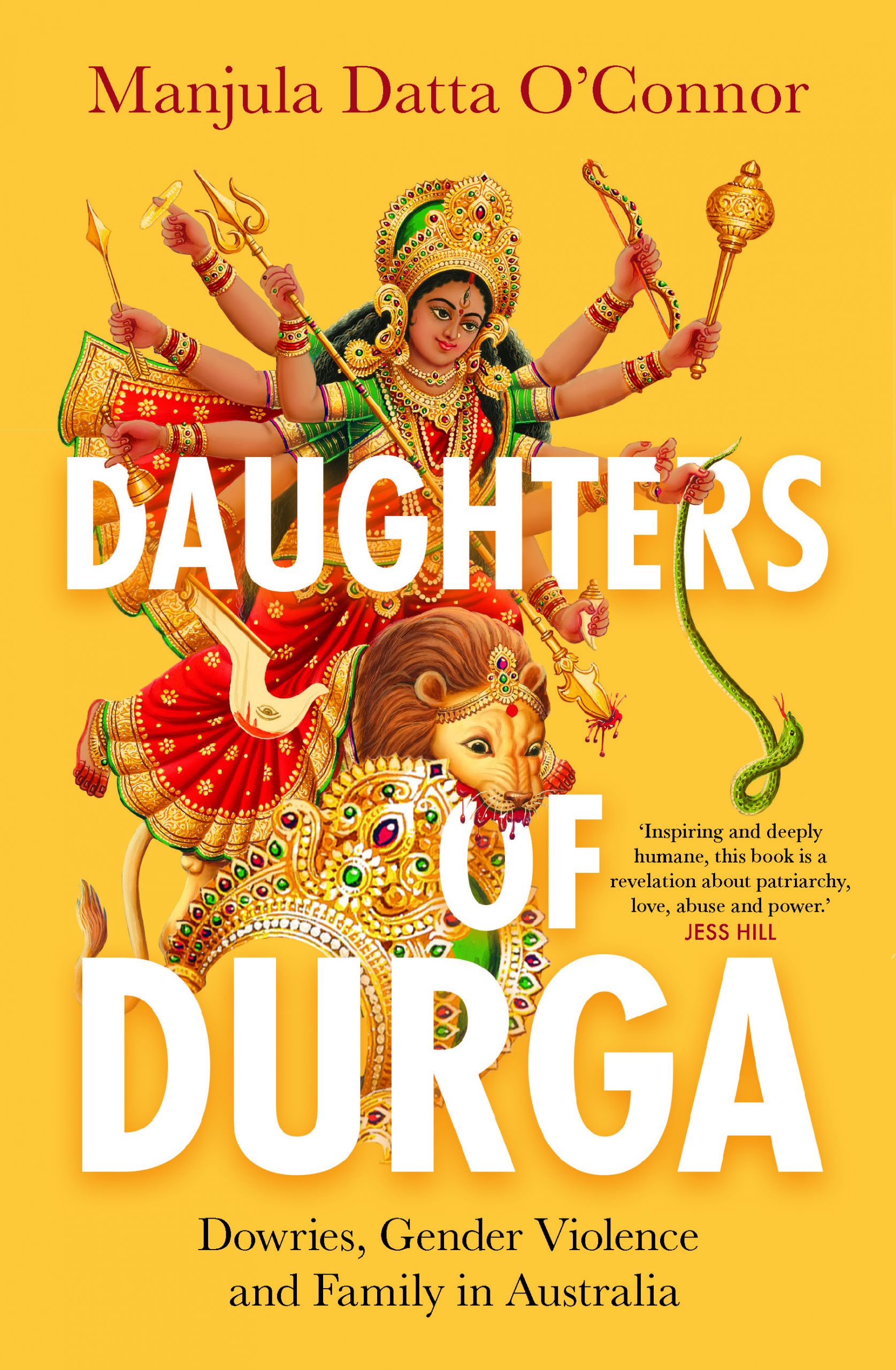

It was in the early 2010’s that a series of domestic violence cases amongst South Asian Communities in Victoria gained traction in the media. Against the backdrop of a rising incidence and awareness of family violence, state and national communities grappled with this emerging profile of what was happening behind the closed doors of South Asian homes. This is where Manjula Datta O’Connor begins her novel, Daughters of Durga, but it isn’t where the story ends.

Manjula is a clinical psychiatrist with a focus on womens’ mental health and family violence. Her work spans three decades and in this time, she has founded the Australasian Centre for Human Rights and Health, given evidence for a senate enquiry into dowry abuse, and been awarded the Victorian Government Award for excellence in delivery of health care to migrant women.

The stories of women impacted by violence are at times difficult to read, but in chronicling the reality of these incidents; how they happened, where they happened, what happened after, Manjula builds a narrative that connects the dots between pre-colonial India to the experiences of migrants of Australia. It is a story that doesn’t shy away from the tragedy of its subject matter but equally, doesn’t linger in despair, instead offering cause and effect and in this, a pathway forward.

Manjula joined the ASAC book club to talk about her writing process, her motivations for writing the book, and key takeaways from working in the domestic violence space as a clinical psychiatrist.

Daughters of Durga paints in-depth portraits of women whose lives have been affected by domestic violence. Though their stories all vary, the legal pathways they take shed light on the systemic patterns when it comes to domestic violence in Australia. One book club member questioned whether the nuances of exploitation as they relate to South Asian communities are picked up by law enforcement in an Australian context. Another noted that GPS technology and increasingly smart ‘smart-phones’ can also become a vessel for manipulation and control.

So for a South-Asian subcontinent with a growing middle class, educational access and economic development, where do exploitative relationships come into the puzzle. In her book, Manjula points to the compounding impact of British colonisation and the way in which engineered local economic depressions had a resounding social impact. One book club member noted that it’s these long held, and often unchallenged views relating to the women’s lives in domestic and professional spheres, live on even after migration.

So what does the way forward look like? Surprisingly, Daughters of Durga asks the reader to look back. Manjula presents the Manusmriti, one of the many legal texts in the Vedas- a directive that conceptualizes a different lived experience of women to the ones they are subjected to in her earlier analogies. Stories like the Manusmriti are important, because they set a local precedent for progress, one that is defined on the terms of country and culture. Equally, so are the stories in Daughters of Durga. Charting the evolution of marriage in an accurate but concise way is no easy feat. But, in doing so Manjula tells a story that offers a way forward, rejecting denial or acquiescence to an idealized national character that doesn’t exist and instead giving readers the tools to consider the whole picture.

Want to join a community of impact driven South Asian Australian women? Sign up here to join a community which supports you and champions your work.